Improving evidence-based critical nursing care in Zambia using the Plan Do Study Act (PDSA) model

Dr Judith Carrier is director of the Wales Centre for Evidence-Based Care: A JBI Centre of Excellence and a reader in primary care/public health nursing at the School of Healthcare Sciences, Cardiff University (CU). Deborah Edwards is a research associate at the school. Dr Patricia Mukwato is dean of the School of Nursing Sciences, researcher and post doctorate fellow at the University of Zambia (UNZA). As a JBI Centre of Excellence, the Wales Centre for Evidence-Based Care is committed to the sharing of evidence-based knowledge and resources to improve global health outcomes.

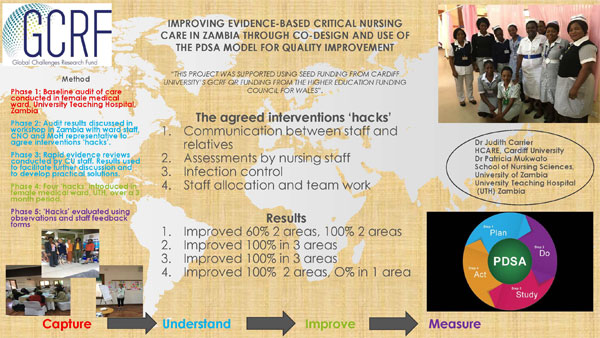

In 2018, Dr Carrier and Dr Mukwato jointly secured Global Challenges Research Funding from Cardiff University to undertake a project titled: ‘Improving evidence-based critical nursing care in Zambia through co-design and quality improvement using the Plan Do Study Act (PDSA) model’. The need for this project was identified following an ERASMUS-funded staff mobility facilitated by the CU Phoenix Project to develop collaborative partnerships between UNZA and CU. The aim of the study was to promote sustainable health and well-being of critically ill patients admitted to an acute care ward in the University Teaching Hospital (UTH) Lusaka, Zambia, through implementation of small evidence-based nursing care interventions, known as ‘hacks’.

Due to limited intensive care beds in UTH, critically ill patients are cared for in the acute ward area with a subsequently high morbidity rate, indicating a clear development need. The School of Nursing at UNZA was in the process of establishing an acute ward area with the aim of ensuring that evidence-based practice formed part of the philosophy of care, using it as a model for teaching nursing students. This project involved five phases and implementation took the form of a three-month pilot project in a female medical ward. Anticipated outcomes were improved nursing care for patients and the development of an evidence-based model of care for teaching nursing students placed in the ward.

Phase 1

A baseline audit of care in the selected ward was conducted by staff from UNZA. This identified key areas of concern and highlighted where adherence to the evidence base could contribute to improved nursing care.

Phase 2

Results from the audit were discussed in a collaborative workshop held in Lusaka, Zambia, facilitated by Dr Carrier, as the principal investigator from CU, and supported by Dr Mukwato, as the co-investigator from UNZA, to share baseline information and discuss and agree on potential interventions. Participants included representatives from UNZA, nursing staff from UTH and a representative from the Ministry of Health nursing department. After the workshop, one participant commented ‘I can now apply the PDSA model during patient care and research’.

Four key hacks were identified from the workshop for rapid reviews:

1. communication;

2. assessment, skills and education;

3. environment and infection control;

4. staff allocation and teamwork.

Following the workshop, further specific audit criteria were developed and an aims statement was devised for the PDSA.

Phase 3

Dr Carrier and Deborah Edwards completed rapid evidence reviews for the hacks at CU, and the results were forwarded to UNZA for discussion with the steering group, led by the co-investigator, Dr Mukwato. The project focused on the four hacks, which were divided into 12 sub-areas (audit criteria) for implementation of evidence-based practice.

Phase 4

Over a four-month period, the four hacks were introduced to the ward area. An orientation seminar was held to introduce the planned changes and the project team provided ongoing support.

Phase 5

A post-implementation audit was conducted.

The project met the set target of 95% improvement in eight out of the 12 sub-areas of implementation. These were:

1. display of patients’ rights and responsibilities;

2. completion of nursing care plans in the acute bay;

3. mentorship for junior nurses and students;

4. orientation for new nurses;

5. display of educational materials;

6. display of infection prevention guidelines;

7. provision and use of infection prevention materials;

8. provision and use of checklists for staff allocation.

The four sub-areas where the set targets were partially but not fully met included awareness of rights and responsibilities by patients, explaining the patient’s condition to at least one relative; and completed nursing care plans in all areas. One area, implementation of regular multi-disciplinary team meetings attended by representatives from all disciplines, failed to show improvement.

Five major lessons were learnt from the implementation process: four enablers and one detractor. ‘Enablers of evidence-based practice should take stock of enablers and detractors and put appropriate measures in place to sustain the former and minimize the latter’, says Dr Mukwato.

Enablers were i) team involvement in the planning process, ii) the need for champion(s), iii) the need for management support and iv) ongoing supportive supervision. The detractor was nurses’ comfort with the status quo. Each of the four enablers had a role to play in the success of the project. Nurses who participated from the beginning of the planning phase, had more buy-in to the project, understood the process well and were more likely to participate.

The weekly supportive supervisory working visit served as a reminder of the expectations of the project and provided mentorship for implementation of certain aspects, for example, the use of communication cards, which was a totally new concept for the ward nurses. One of the nurses commented, ‘Our ward is now being admired by other nurses, now that we have materials for infection prevention and other resources’.

The mentorship team provided hands-on mentoring on patient assessment, identification of patient problems, formulating nursing diagnosis and documenting care on the care plans. Management also provided an enabling environment for implementation. The nurse in charge played an essential role, championing and leading the project.

The observed detractor was the comfort with status quo for some nurses who were resistant to change. Following the pilot, a celebration event was held for the staff, where the chief nursing officer commented, ‘Today’s luncheon is being hosted for the nurses in E12 in recognition of their hard work and good output. The permanent secretary did a spot check on Sunday afternoon and found the ward to be well organised. Thanks. Team efforts are bearing fruit.’ Whilst further rollout has been challenging since the initial pilot was completed, the model of care for mentorship and orientation, nursing process and infection control have been sustained on the ward.

Further resources

Cardiff University Phoenix Project.

Kings Fund (2008) EBCD: Experience-based co-design toolkit.

NHS Improvement (2017) Quality, Service Improvement and Redesign Tools: NHS Improvement Plan, Do, Study, Act (PDSA) cycles and the model for improvement

NHS Hack Day

Authors

Dr Judith Carrier1,2, Deborah Edwards1,2, Dr Patricia Mukwato3

1 Wales Centre for Evidence-Based Care: A JBI Centre of Excellence

2 School of Healthcare Sciences, Cardiff University

3 School of Nursing Sciences, University of Zambia

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this this World EBHC Day Impact Story, as well as any errors or omissions, are the sole responsibility of the author and do not represent the views of the World EBHC Day Steering Committee, Official Partners or Sponsors; nor does it imply endorsement by the aforementioned parties.